2006

Vera Lutter’s images of a the Rheinbraun coal mine track energy production—the source of modern industrial accomplishment—to its geological root. Her images of enormous land-levelers complement her earlier project photographing London’s Battersea Power Station in 2004. In Battersea, an inoperative coal processing plant is shown in a state of noble ruin. Sites of industrial activity often recur as subjects of Lutter’s work, underscoring the relationships between technological ambition and the transformation of the earth’s surface both in urban and isolated environments. Likewise, the artist’s use of analog photography points to the parallel of the medium’s beginning and western industrialization.

The effect of a constantly growing population trying to improve its standard of life forces society to reach for new resources while still laboring to maintain its old ones. Stripped from the surface of our planet since antiquity, brown coal is one of the oldest energy supplies known to man, and over the course of centuries, humans have started to dig deeper and deeper to seize this dwindling fossil fuel. Near the rural town of Hambach, Germany, the energy company RWE (Rheinisch Westfälische Energiewerke)—formerly Rheinbraun—harvests coal from 300 meters beneath the topsoil.

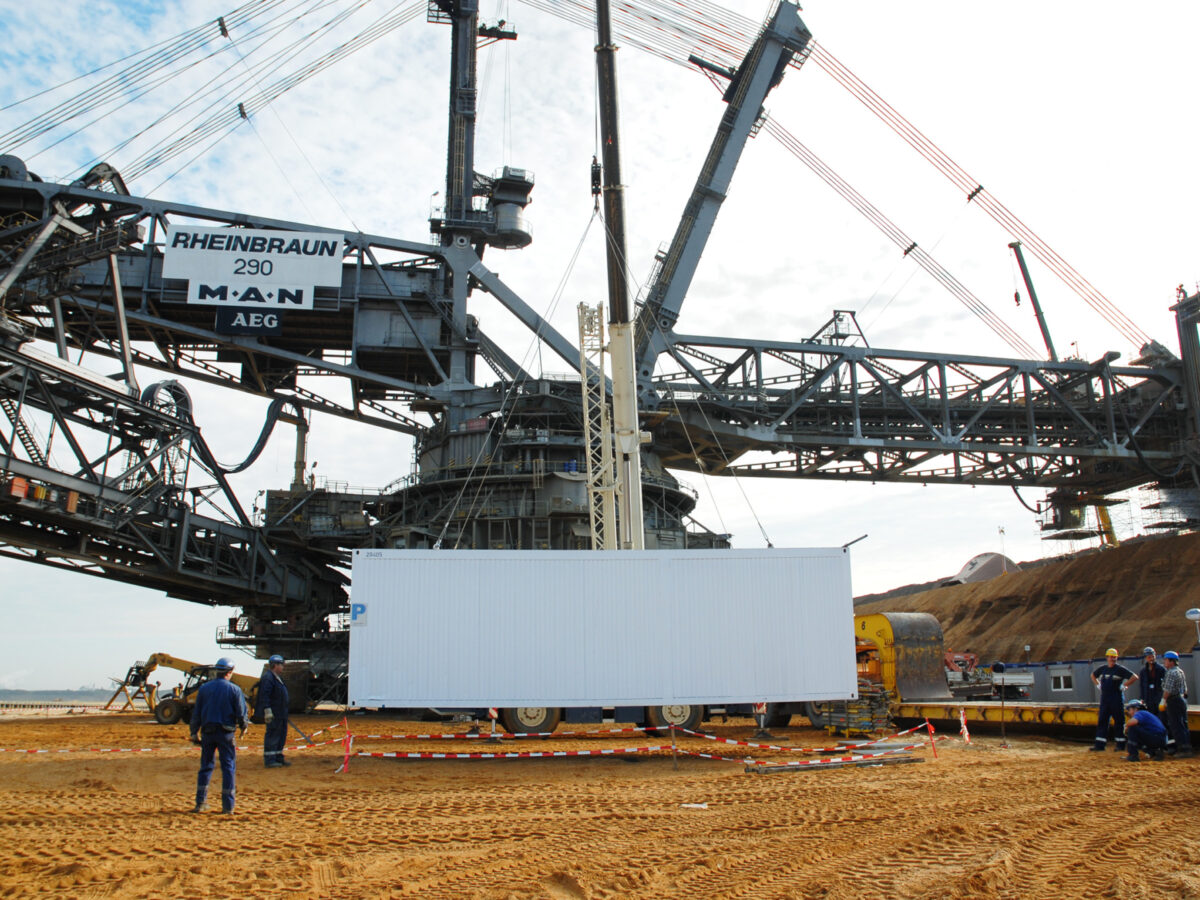

Due to the specific circumstances in which brown coal is embedded in the ground, the material must be shaved from the surface of the land in a process similar to strip mining. This procedure requires the removal and relocation of enormous amounts of soil and sand to gain access to the coal. Gigantic machines, like the 220 meters long bucket wheel excavator seen in Lutter’s images, have been developed to carve soil and excavate the lucrative coal reserves. Where villages were relocated and mountains were turned into valleys, elliptical patterns are dug into the landscape creating terraces of soil, sand, and dust that extend as far as the eye can see. This process destroys the fragile structure of naturally layered soils and root systems, turning the mine into an enormous mud pit during rainfall, and into a desert-like, infernal cloud of dust in the dry summer months. All vegetation has disappeared from the mine site. The landscape is both devastated and redesigned.

Lutter’s images explore both the capabilities of an industrialized civilization and the sites where such efforts culminate in ruin. Working with a forty-foot shipping container as a camera obscura, her photographs reflect the immensity of this undertaking. In the images, one finds the sublime not atop a mountain but through the astounding mechanization of modern industrial accomplishment. Though Lutter does not show the vast pits created by the excavating machines, the viewer sees the machine’s track marks across the barren earth stretching to the edge of the photographs and insinuating the disfigurement of the land extends far outside the frame. Yet this deformation to the landscape is not without order or even beauty to which Lutter’s works testify, but it is a kind of cautionary beauty, manifesting both the desirable production of energy and all its waste. It is this dichotomy of seduction and repulsion that lends her work its paradoxical edge. Lutter’s pieces, of which some are close to twenty feet in length, not only give evidence to the monumentality of the mining project but also reflect the haunting sublimity found within this system of destruction and recreation.